Problem Set Up

Suppose we have a Linear SVM with a hard margin, and

\[H(x) = \mathbf w^T\mathbf x + b\]

is the hyperplane that serves as the boundary function. The vector $ \mathbf x $ represents an instance of the feature space. Show that the size of the margin, $ M $ is

\[\frac{2}{||\mathbf w||}\]

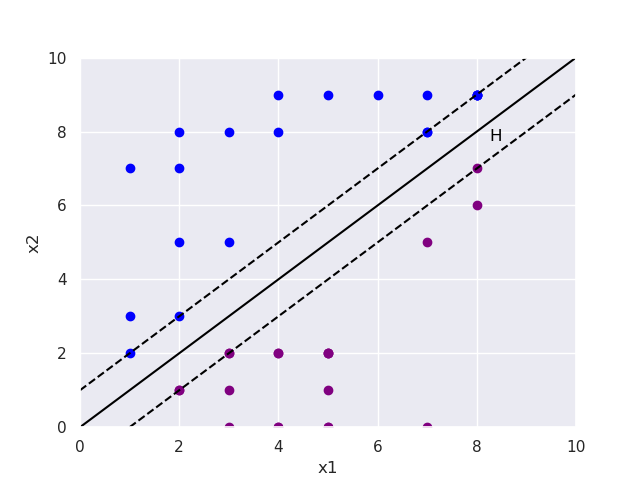

Here is a quick visual to help grasp the problem at hand:

The Normal Vector w

So we need to know the distance between the two dashed lines. Great! The shortest distance from one of those lines to the other is a straight line that is also orthogonal to any point on the boundary function $ H(x) $. Is there anything given in $ H(x) $ that represents a vector normal to $ H(x) $? Spoiler, its $ \mathbf w $.

Lets assume we have two points on the boundary function. Call them $ \mathbf x_{i} $ and $ \mathbf x_{j} $. Since they lie on the boundary function we have:

\(\begin{equation} \tag{1}

\mathbf w^T\mathbf x_{i} + b = 0

\end{equation}\)

and

\(\begin{equation} \tag{2}

\mathbf w^T\mathbf x_{j} + b = 0

\end{equation}\)

if we subtract (1) and (2) we have:

\[(\mathbf w^T\mathbf x_{i} + b ) - (\mathbf w^T\mathbf x_{j} + b) =0\]

or

\[\mathbf w^T\mathbf x_{i} - \mathbf w^T\mathbf x_{j} =0\]

\[\mathbf w^T\cdot(\mathbf x_{i} - \mathbf x_{j}) =0\]

This is a vector that lies along the boundary function dotted with $ \mathbf w $. We also know that the dot product of two non-zero vectors $a$ and $b$ is:

\[\begin{equation} \tag{3}

\mathbf a \cdot \mathbf b = ||\mathbf a|| ||\mathbf b||\cos(\theta)

\end{equation}\]

Where $\theta$ is the angle between $\mathbf a$ and $\mathbf b$. Since $\mathbf w^T\cdot(\mathbf x_{i} - \mathbf x_{j}) =0$ we can conclude that $\mathbf w$ is orthogonal to $\mathbf x$.

The Dot Product and Vector Projections

So why did we need to prove to ourselves $\mathbf{w}$ was orthogonal to $H(\mathbf x)$? Because we wanted the shortest path from a data point on the edge of the boundary to $H(\mathbf x)$, and the direction that leads us to the data point the quickest from the boundary function is orthogonal to $H(\mathbf x)$ or in the same direction of $\mathbf{w}$. That’s cool.

Now we have to find a way of representing our data point $\mathbf x$ in terms of $\mathbf w$. We can do this with our definition of the dot product above in (3). If we divide (3) both sides by $\left\lVert \mathbf {b} \right\rVert$, we have:

\[\begin{equation} \tag{4}

\frac{\mathbf a \cdot \mathbf b}{||\mathbf b||} = ||\mathbf a||\cos(\theta)

\end{equation}\]

We can interpret the right side of (4) as the magnitude of $\mathbf a$ projected on the direction of $\mathbf a$. Note that dividing by $\left\lVert \mathbf {b} \right\rVert$ on the right hand side is the dot product of $\mathbf a$ in the direction of a unit vector $\frac{\mathbf b}{\left\lVert \mathbf {b} \right\rVert}$.

Noice. Now how do we apply this into our problem? Remember that there is a dot product in $H(\mathbf x)$. So if we wanted to know $\mathbf x$ projected onto $\mathbf w$ we would need to divide $H(\mathbf x)$ by the magnitude of $\mathbf w$:

\[\begin{equation} \tag{5}

\frac{|\mathbf w^T\mathbf x + b |}{||w||}

\end{equation}\]

Woah, what’s with the absolute value signs and the $b$? Well, we’re only looking at one side of $H(\mathbf x)$ in our derivation. Remember that on one side of $H(\mathbf x)$ all the data points have a positive sign and the other side has a negative sign. The absolute value takes care of the negative sign since we’re only concerned about the distance. The $b$ can be thought of as an offset. It shifts our boundary function up and down, but would not affect the dot product of $\mathbf x$ and $\mathbf w$. Just like the equation of a line and the y intercept. Almost there!

Lets consider the positive side of our boundary. An SVM labels a data point positive one if it lies on the positive boundary or beyond that boundary. Therefore, our numerator in (4) is equal to 1 since the SVM is only concerned with the label. So, the distance from $H(\mathbf x)$ to the positive boundary is;

\[\begin{equation} \tag{6}

\frac{|1|}{||w||}

\end{equation}\]

A similar reasoning for the distance from $H(\mathbf x)$ to the negative boundary would give us:

\[\begin{equation} \tag{7}

\frac{|-1|}{||w||}

\end{equation}\]

We were originally asked for the full boundary length so we have to add (6) and (7) together to get:

\[\begin{equation} \tag{8}

\frac{2}{||\mathbf w||}

\end{equation}\]

QED baby!

Tying this All Up

Congratulations! You made it to the end of this long and dense post. So why does this matter? Other than it tickled my brain.

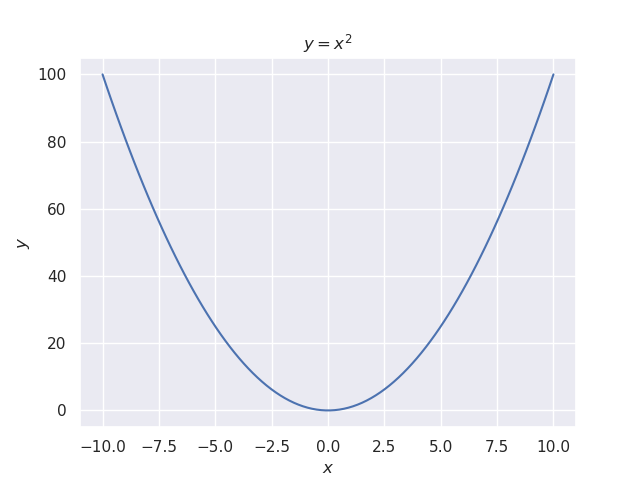

Well, this result made the optimization problem for SVMs a lot easier. We want to maximize our margin in an SVM, and we have a very interesting result about the length. To maximize our margin we’d have to minimize our $\mathbf w$ in (8). So we can transform this problem into minimizing $\left\lVert \mathbf {w} \right\rVert$ since (8) is scaled by a constant and the reciprocal of $\left\lVert \mathbf {w}\right\rVert$. To make it even easier we can minimize $\left\lVert \mathbf {w} \right\rVert^2$. Why is this easier? Think of a quadratic equation in 2D:

There’s a global minimum! Thank’s for reading.